|

|

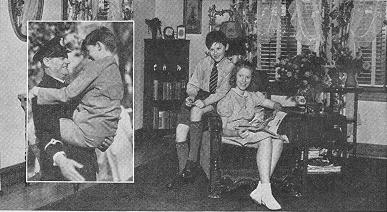

He’s a normal twelve-year-old. Like others of his age, this gentleman prefers gore. Asked his opinion of "How Green Was My Valley," he said: "It seemed to go very well." "Yes, but how did you like it, Roddy?" "Well, I don’t really care much for that kind of picture. Not enough bloodshed. I’d rather see a whodunit." The face may be wistful, but the spirit isn’t. It’s not lonely communion with his soul which gives his eyes their dream-haunted look. Remarkably well-adjusted to this world, he has only one improvement to suggest — extermination of Hitler and gang. All this being so, there remains the mystery of his acting, mature beyond that of many grown-ups. To call him a child actor falls wide of the mark. He’s an actor who happens to be twelve, but who conveys emotion with the sureness of experience and the sensitivity of understanding. It’s a mystery that can’t be wholly explained, any more than you can explain the young Mozart. A child is born with a gift. But Roddy’s parents are partly responsible — if not for the gift, then for helping to mould an integrated personality which can use its gift to the best advantage.

RODDY’S father came from a strictly regulated home. His mother spent much of her girlhood in boarding schools. For their children, they decided before they ever had any children, things would be different. From the time consciousness dawned, Roddy and Virginia were treated like human entities. They lived not merely under their parents’ roof, but with their parents. They weren’t shunted off to the nursery or banished with relief at six because it was bedtime. No Sunday invitation was accepted without consulting them. They had the same right as their elders, the McDowalls contended, to choose not to be bored. Each relished the society of the other three. There happened to be no other children in the neighboring houses on Herne Hill where they lived, so Roddy and Virginia invented their own games and played them together.

|

Mrs. McDowall grew weary of being told that her child was marvelous and ought to be in films. "How does one go about it?" Nobody knew. At length she took matters into her own hands. A columnist wrote that Monty Banks needed a boy for his new picture with Gracie Fields.

As Roddy tells it: "Mummy phoned him up and he was quite rude to Mummy. He said, ‘You’re the nine hundred and ninety-ninth person to phone me up today, how’m I to know where Monty Banks is?’ So Mummy said, ‘If you print such things in your column, you must expect to have people phoning you up.’ Well, probably seeing the logic of that, though still cross, he said: ‘I left him at the Dorchester half an hour ago and for all I know he’s still there.’ So Mummy said, ‘Thank you very much,’ and then she said, ‘I don’t suppose I’ll get him, but there’s no harm in trying.’ "Well, curiously enough, she did get him and he was very nice and said send some photographs. But I was too small or something was wrong with me and I didn’t get the part. However, he advised Mummy where to go and I finally got in a film by the name of ‘Scruffy.’"

HE continued his new career till the war. He knows what bombs are like. "They whistle," he says, "like a thousand people screaming." Air raids don’t scare him. "Beforehand, you think, I wonder what it’s going to be like. The first raid we ever experienced was in somebody’s house and the man ran around saying nobody get nervous, and Mummy just looked at him, and I looked at Mummy, and she wasn’t scared, so neither was I."

|

Back | 1 | 2 | 3 | Next

RM Tribute: Frames | RM Tribute: No Frames | Contact Us | Musgrave Foundation