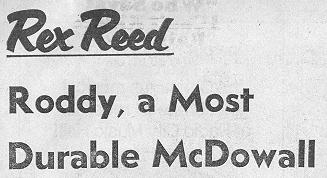

CONTRARY to popular belief, Roddy McDowall is not Peter Pan. He is 43 years old, and if you get close enough to the elfin ears and the Puckish grin and the thick horn-rimmed glasses that make him look like a startled mongoose, you’ll notice indications in the ridges of his mischievous face that he has lived. Twenty-eight years ago, when he was 15, he broke millions of hearts in "Lassie Come Home" and "My Friend Flicka." A lot of water has passed under the bridge since then—70 movies, 25 Broadway plays and hundreds of TV shows in which he’s played alcoholics, bums, murderers, fairies, apes, cowboys, war orphans and just about everything else you can think of—and Roddy McDowall has survived valiantly. So well, in fact, that he’s just directed his first motion picture – a bizarre fantasy with Ava Gardner called "Tam Lin." It’s not a great film, but it has the definitive mark of a man who knows and loves movies. The instant you step into his rambling, cluttered apartment high above New York’s deadly Central Park, you know he fits both descriptions. The place looks like one of those English country houses that bulge with Georgian silver, crocheted doilies and cabbage roses (and more often than not smell like rancid butter and old socks). I have never seen so many dust-catchers. "La Boheme" soars from a phonograph. A jolly black housekeeper serves ice water in a crystal goblet. Tables and desks crumble under the weight of every conceivable object. Papers, magazines, stills, posters, ashtrays and movie memorabilia crowd the rooms and hundreds of frames of autographed movie star pictures line the walls. Bookcases sigh with dusty volumes of movie ads clipped from old movie magazines, autographs of every celebrity he’s ever met ("Roddy," says a friend, "doesn’t know anyone who isn’t."). It is a palace of trivia, ruled by one of the world’s great movie buffs. Cards fall from the bindings of books onto the floor. I pick them up and they are signed "Richard Barthelmess" and "Buster Keaton." I reach for a cigaret in a silver box and the engraved inscription reads: "In fond remembrance of ‘Sunny’ from George Gershwin." The place is a bloody museum. "That was Marilyn Miller’s cigaret box," he grins. "I’m a nut. An absolute nut. I collect everything. I came to America in 1940, when I was 12, and two weeks later I had the part of the boy in ‘How Green Was My Valley.’ I’ve been a movie nut ever since. When I was 13, I wrote Pola Negri a fan letter and she turned up at my house. The first person I ever met was John Barrymore. He was very drunk." THE ROOM we’re sitting in turns into a screening room at night, and if you’re one of the "in" crowd in New York, you get to join people like Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden, Adolph Green and Myrna Loy for an evening of movies at Roddy’s. He and Mel Torme have two of the best private collections of movies in show business, but he is reluctant to talk about it. "I can’t allow the names of my films to appear in print or some movie studio will send lawyers around to make trouble. They don’t care about the films, they just care about your right to own them. Have you any idea how much nitrate film is disintegrating in vaults? They’d rather see it burn than be enjoyed by people for centuries to come. Hollywood has never preserved its own history. If it was not for private collectors, most of the great masterpieces would be gone forever. I asked for some of my early films and they told me to go … "Wouldn’t it be fascinating to see the out-takes of great movies? When something is cut it’s sent to a warehouse. The director’s job is over, three or four years go by, even the man who edited the film is gone, the notes and records are lost. When I did ‘Cleopatra’ in Rome, I watched it go through many versions. All that film is lost forever. Judy Garland’s famous ‘Lose That Long Face’ number that Jack Warner recklessly chopped out of ‘A Star Is Born’ is somewhere rotting in a vault, but nobody can find it. Think how interesting it would be to see all the screen tests of great stars. They exist somewhere, but nobody knows where. It’s up to private collectors like myself to preserve as much of that history as we can." It’s like a kind of movie ecology—saving films instead of trees. "I’d like to see it all compiled in a Hollywood museum, but nobody out there cares. They all laughed at Debbie Reynolds when she tried to buy up all that stuff from the MGM auction and start a museum, but she really had the right idea. The only answer is to donate everything to libraries. Bette Davis and I are giving everything to Boston University. I’m giving them every script from my film, the clothes I wore in ‘Lassie Come Home,’ even the hat Stan Laurel gave me as a child." And, one presumes, eventually the entire Errol Flynn estate, which he just bought, including Flynn’s film library. ONE REASON he knows and cares so much about movies is that he inhaled them like oxygen all his life. "That myth about child actors doomed to failure is nonsense. I survived because I never felt like a kid put upon by neurotic parents. I loved it. After I was evacuated from England, I never went to a public school again, but it had no ill effects. I sat around on sets and learned from Anna Q. Nilsson and Mary Pickford." He also knew when to get out. When he was 22, he left Hollywood, came to New York, got into the heyday of live TV and did Broadway shows like "Compulsion" and Noel Coward’s "Look After Lulu." He also got into photography. At first he was kinky for statues, buildings and animals. Then he started photographing his friends in their environment. Since his friends were people like Noel Coward, Marlene Dietrich, Elizabeth Taylor and Natalie Wood, it all fell into place. He became one of the highest-paid photographers around (mainly because he's the only person people like Chaplin and Mae West will allow to take their picture) and the result was a great book called "Double Exposure" that took three years to assemble. |

It is now a collector’s item, adorning some of the most sophisticated coffee tables in the world, in which he enlisted famous people to write their impressions of other famous people, all of whom were then photographed by Roddy McDowall. "The whole thing finally got out of hand because I didn’t know who to include and who to leave out. And everyone wanted to read what other people wrote about them. I had a rule that nobody was allowed to read anything until the book was published. The only exception I made was Montgomery Clift. I was sure Monty would die and I wanted him to see what Marcello Mastroianni had written about him."

|

|

SUNDAY NEWS November 21, 1971 |

|