|

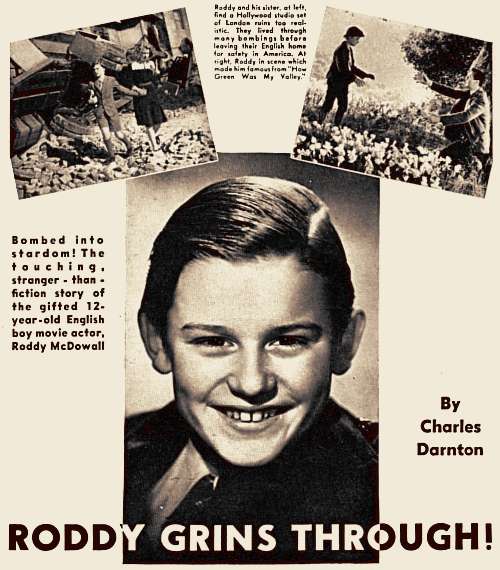

One blackout night in London a tearing, jagged split of bomb came crashing through the roof and slugged down at their very feet. And so it was that Roddy and his sister came to Hollywood.

Not that a boy of 12 and a girl who was only a year ahead of him had anything to say about it. Mr. McDowall, as Roddy blistered his hand snatching up the hot, ugly intruder, said things were getting too close for the good of his children and that it was high time they were hurried off to a place of safety — America. His wife, sweeping up the dust of fallen plaster, stoutly agreed with him.

For that wasn't the first time their house at Herne Hill, not far from Croydon — perilous as a powder-key because of its airport — had been hit. Not by a long shot. There were no windows left in it, and a particularly mean blast had ripped the lock clean out of the front door, so that anyone could walk right in whenever he jolly well pleased.

"Daddy got tired of mending the holes in the roof," Roddy matter-of-factly told me.

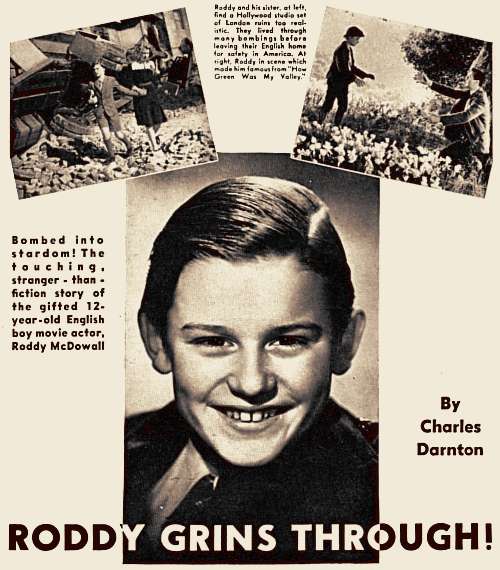

Hearing this was like seeing through those holes into an English home that again and still again raiding Nazis had made the scene of attempted murder. Out of that home, by the strange fortunes of war, was to come an obscure child destined to be known in a country that still was a strange land to him as the most gifted boy-actor of today. For that, no less, is what his truly fine performance of Huw in "How Green Was My Valley" now has made Roddy McDowall.

Yet all that this four-foot-eleven, ninety-pound bundle of talent had to say to that was, "First, I had a nice tiny little scrap in 'Man Hunt,' but Huw is a splendid part."

Quite unspoiled, Roddy gave no credit to himself, only to the role that was to make him a star in "On the Sunny Side." Nor did money seem to interest him in the least, though Hollywood, which talks even more than money itself, was saying his salary would be $2,000 a week.

"Oh," he exclaimed, "I'll be a hundred and five when I'm earning two thousand a week! And Virginia will be a hundred and six, because, you see, we always share and share alike."

With this went a smile. And, aside from his acting, Roddy's smile is the most remarkable thing about him. Vividly, it lights his pale, sensitive face like a sunbeam and brings a dancing sparkle into his keen eyes, darting through an occasional fall of darkish hair.

"But maybe," he hoped, "I'll be able to help Daddy put a new roof on our house. That is, when there's no more bombing of London."

It was easy enough to think of his having been bombed into stardom. But, as we talked of the rain of destruction he had come through, I was wholly unprepared for something that followed, something that brought out the real boy in Roddy as nothing else could have done. Digging into the pockets of his tweed jacket, he proudly showed me a bomb fragment and a piece of shrapnel! These grim keepsakes he evidently lugged about with him daily, just as an American boy stuffs horse-chestnuts into his jeans.

For his "interview," as he solemnly called it, Roddy had perched himself dutifully on a wall-bench in an office at the Twentieth Century-Fox Studios. He was sitting bolt upright, with his knickerbockered-legs straight out in front of him. It struck me that his stiff position wasn't the most comfortable in the world for a boy, and after a while I detected a slight wriggle, most polite, though unmistakably a wriggle, so I suggested he might like to get down and limber up.

"Thank you," he gratefully beamed. "I should like it very much," and he was on his feet in a single leap.

Through the door at that moment edged a fair-haired, slender girl, rather quiet or merely shy, perhaps a bit of both. Roddy caught her hand and eagerly brought her forward, with: "My sister, Virginia."

As the two children stood fondly together, I noticed that the girl was a full head taller than her brother.

"I'm so sorry — for Virginia, I mean," said Roddy, following my eye. "We were exactly the same size when we came to Hollywood, and so Virginia was chosen to play Ceinwen in 'How Green Was My Valley.' Then the production of the picture was postponed for six months, and during that time Virginia grew three and a half inches — imagine that! It's such a pity, for she grew herself right out of the part. And I think she's very good. But, anyway, we always divide what we make, so she has half of my salary."

"I also outgrew twenty dresses I brought over for pictures," added Virginia, taking the inevitably feminine angle. "They don't fit now and they can't be lengthened. But," brightening, "I'm very happy about it, because I like American clothes better. Of course, it was absurd of me to grow the way I did."

On the other hand, it seemed to me that she, not to mention her brother, might well have been scared out of a year's growth by crossing death-haunted waters.

"I was scared stiff in London," confessed Virginia. "But on the ship I was so seasick that I was too busy to be frightened. Anyway, it might have been far worse for both of us. When war was declared, an agent hoped to sell Roddy for American pictures, and I was to go along, as we have always been together in our work since we were five and six. If that arrangement had gone through, we both would have been on the Athenia." She shuddered at the thought of the helpless little ones who had been plunged into eternity when that brave craft on its errand of mercy was struck a mortal blow. "Roddy was too interested in what was going on, both in London and at sea, to be afraid."

"Of course, I knew it was dangerous," granted Roddy, "but I didn't worry much. At home mattresses were a protection from splinters, unless there happened to be a direct hit. Before leaving London we hadn't been to bed for seven weeks. We just dragged mattresses into an old cupboard under the stairs in the back hall, and all of us managed to sleep there fairly well. You know, you can do almost anything if you only set your mind to it. We really weren't actually uncomfortable, at least on reasonably quiet nights. All that time Virginia and I still were in English pictures and making daily trips to studios. One day when we were returning from fittings in a train going from Oxford Circus to the Elephant and Castle all passengers were called out at Piccadilly. But it wasn't a very good air raid."

"By a 'good' air raid," duly explained Virginia, "Roddy means a bad one."

"For that matter," he insisted, "we had a lot better ones right at home. At a studio we'd stop work and go right into a shelter, and that was a nuisance, just dull."

"A bit stuffy," amended Virginia. "Roddy always wanted to be outdoors when a raid was on so that he could watch it, and Daddy had an awful time getting him in off the street."

"It was exciting to watch," glowed her brother, "and I didn't want to miss anything. You only get something like that once in a lifetime."

"That's often enough for me," Virginia was content to say.

But even this was said with a smile, as though it were her little joke. The calm way in which those two youngsters talked of life-and-death matters revealed to me, as nothing else could have done, the British attitude generally toward the gigantic struggle it is making. Still, it seemed they must have been filled with dread of facing the perilous voyage they had made.

"We got away at a rather exciting time," was Roddy's only admission. "There had been four hours of raid the day before we left, and our house was hit by a lot of two-inch shrapnel. Then, on the morning we started for Liverpool, there was another raid at Euston. Things at the railroad station were pretty lively. That made getting off by train an awful nuisance. Oddly enough, we arrived at Liverpool in the midst of a raid. We had to wait there a week, and for five days while we were at the hotel there was a raid with every meal. Kept always on the buffet was a large card, and when anything happened it would be turned over with its lettered side reading 'Air Raid Now in Progress.' That meant you had to stay right where you were — in the dining room."

"And that meant more ice cream for me," interrupted Virginia. "One day I had three dishes. My appetite was good, so I was happy to stay there. And when I went out into the streets I was very interested in the signs I saw. One, on a partly blasted place, read 'Shop More Open Than Usual,' while another said, 'We May be Shuttered, but We're Not Shut.' I thought them very funny."

Both even boarded the boat without fear except for the father they were leaving behind. With bombings still going on, the ship lay at anchor for two days. One bomb exploded only fifty yards away.

"That gave me a great thrill," said Roddy.

"It was impossible to keep him off the deck," said Virginia, reprovingly.

"Well," argued her brother, "that was the only place where one could see things. One day, through glasses, after we'd got under way, I saw some porpoises — at any rate, that's what I thought they were. But they weren't really. They turned out to be submarines. Wasn't that a funny mistake to make?"

By that time, it developed, Virginia had taken to her berth, sick. "We had twenty-four hours of bad storm after getting out of the submarine zone, where we'd been for three days," she reported. "I slept through most of it."

"Virginia was in the top bunk," related Roddy, "and one night of the storm she popped out like a shot and came down like the stick of a rocket. It was a bit of luck that I just managed to catch her. They wanted her to recite at the ship's concert, but she didn't feel up to it. I was terribly sorry, because she was given a medal at school for reciting Shakespeare."

"So were you," his sister reminded him.

When I asked whether he had recited at the concert, Roddy said he had given "The Sea is His." At the incidental auction of unknown quantities he won a bottle of whiskey. "Of all things!" he marveled. When I wondered what he had done with his prize-package he replied, "I gave it to a sailor."

H. G. Wells was one of the passengers, and Roddy met him on the deck.

"Did Wells talk with you?" I inquired.

"He said," quoted Roddy, " 'Hello, where are you going?' "

"Not exactly chatty, eh?" I remarked.

Again that flashing smile, then a laugh that bespoke a full-grown sense of humor. It was equalled only by his courage. Here was a boy, I concluded, who throughout his entire eventful journey to Hollywood had been absolutely unafraid.

"Oh, no," he hastened to say. "I was afraid of New York."

"Its size?"

"No, its lights. They seemed so dangerous. I suppose that was because they would have been in London. We'd had blackouts so long that now lights terrified me. I sort of wanted to go and put them out. They made me feel uncomfortable. And without lights, you see the stars much better."

I couldn't help feelilng that the poet in this boy was speaking. But when I asked what he liked best of all in America he said, "Laurel and Hardy."

"And you?" I inquired of his sister.

"Chocolate milk sodas," promptly answered Virginia.

I wished her a good part so that she would be able to buy herself many sodas.

"Oh, that doesn't matter," Roddy assured me. "You know, we always share and share alike."

In token of which those devoted youngsters walked off hand-in-hand.

|